Case Studies

Kerry Hudson

"In a country like ours, there is an expectation that when a crime is alleged to have been committed, justice will be served in every case. That everyone has the right to put forward a defence and have a fair trial. Unfortunately, as a solicitor working in the criminal justice system, I can no longer guarantee that.

Legal Aid exists to make sure that society's poorest and most vulnerable people can still have access to proper legal advice. It is a basic human right. But after years of being chipped away by government cuts, this system is close to being completely broken.

Many accused people now spend months or even years "released under investigation" by the police before they are charged. Imagine how this feels to victims of rape or assault. Trials in the Crown Court (where the most serious cases are heard) are now being listed into 2023. The upshot is that many cases are taking four or five years to make their way through the system – it's backlogged as if someone were standing on a hosepipe.

The pandemic has only made the situation more difficult. A reduction in the number of days that Judges sit means trials are delayed for years at a time. Since most of this work is for a fixed fee (regardless of how long a case goes on for) and law firms are not paid until a case concludes, lengthy delays seriously affect cash flow. The bottom line is that there is no money for administrative support or to train the next generation of Legal Aid solicitors.

Even the most die-hard grassroots Legal Aid lawyers, who really care and believe in the system, have started to give up on practising publicly funded criminal work. It is hard enough working long, unsocial hours on difficult and emotionally draining cases, but when you can't afford to pay your rent each month, or pay down your student debt, I can no longer see what incentive the next generation of young lawyers has to come into this area of law.

The average age of a duty solicitor – the ones who appear in police stations and who are, quite literally, the first line of defence – is close to 50 years old. Who is going to replace them? If justice is not adequately served at the outset, the cost to the public purse in fighting appeals, compensating victims and fighting miscarriages of justice, will be enormous.

It is now not uncommon for us to struggle to find a barrister able to represent a client in court and trials are routinely being abandoned due to a lack of criminal advocates for both the Defence and the Prosecution. I have never before experienced this in my career.

To be tough on crime requires long-term investment at all levels of the criminal justice system, including those undertaking defence work through Legal Aid. It is a delicately balanced system which requires each part to work together to achieve justice. If one part stops working, the whole system quickly grinds to a halt."

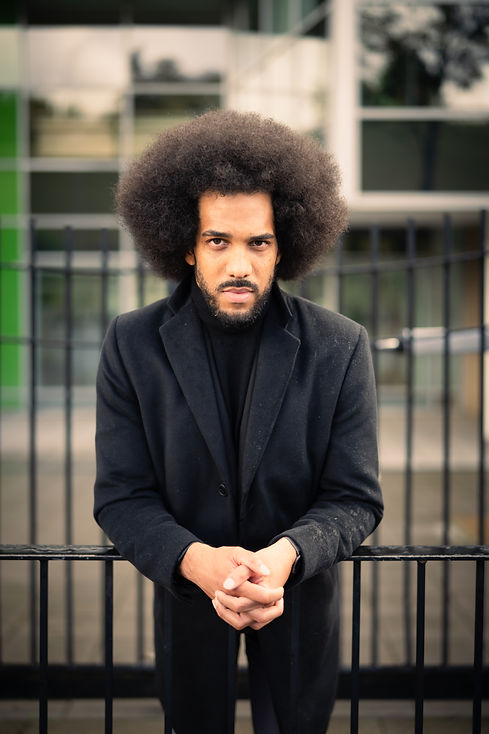

Michael Etienne

“We know that excluding children from school has catastrophic effects. These decisions demand the most scrupulous adherence to the principles of natural justice by the head teachers who make them and the governing bodies who ratify them. In truth, this is far from reality. We know that exclusion can ruin a child’s education prospects, exposed as they become to what the Commons Education Committee has reported as the “Forgotten Children: alternative provision and the scandal of ever-increasing exclusions” (2018). Year on year, rates of exclusion, both temporary and permanent, have been rising, a trend that started in 2012.

In 2013, publicly funded advice for parents and children affected by exclusions was taken out of the scope of legal aid. Since then, the number of publicly funded education law advisers has dwindled from an already low base of 28 providers, to just ten. The result is that children and their families face potentially life-defining decisions, but are excluded, first from school and then from accessing justice.

I have worked on so many distressing cases over the years. One of the most poignant for me was one for a Black pupil, whose every transgression was recorded as “persistent misbehaviour” and who was readily described as “aggressive” but then not seen as the victim of a racist assault when he was targeted by other pupils because of his afro hair. For this boy, being represented by anyone prepared to stand up for him was a revelation – made more profound for it being a Black barrister. His eventual reinstatement was secured only because he had a legal team acting free of charge, at a hearing that lasted several hours into a Friday evening and after arguing detailed legal submissions. Most families can't access anything like this.

In the past few months alone, serious case reviews have established a link between school exclusion and criminal exploitation in the deaths of two teenage boys, Jaden Moodie and Tashaun Aird. Exclusion is often the first step down a road towards exposure to the worst of the criminal justice system.

Even while it was said to be imperative to re-open schools in the interests of children, in the face of the Covid-19 pandemic, the law and practice of exclusion has remained untouched. The children persistently over-represented in all forms of exclusion are wearingly predictable: those who receive free school meals, those with special educational needs, Black children and members of traveller communities. They are many of the same children likely to have been disproportionately affected by the disruption and grief wrought by Covid-19.”

Sally

"I was taken to court by my ex who wanted contact with our children. Because of what he had done to them, I knew that any contact at all would place them at very serious risk and I knew I had to do all in my power to protect them."

Sally’s two small children suffered horrific sexual abuse at the hands of her ex-husband. When they split, he applied to the court for contact and Sally was terrified for them. As a single mother she earned £18,000, which she used to cover rent, utilities and food, leaving her with next to nothing at the end of each month. Yet she was deemed ineligible for legal aid because she earned too much.

Sally faced the first hearing alone while her husband had both a solicitor and a barrister representing him. He smirked at her in court and she felt physically sick, not understanding the law, court procedure or how to defend herself and safeguard her children. When the court took a break she tried to google the terms that were being used in an effort to make sense of what was happening. In desperation, Sally contacted several different solicitors to see if she could cobble together some help from free half hour sessions, but it proved impossible.

With a huge stroke of luck, one of the solicitors she contacted was Jenny Beck, who takes on a few cases each year for vulnerable clients who are unable to pay for advice and can’t be helped under the legal aid scheme.

Together they also found Sally a barrister, Victoria Haberfield, who was so moved by her circumstances that she represented her in court for free. Sally was finally armed with a legal team equal to that of her husband. The Judge found that the abuse was so grave and the risk posed so great that her ex should have no contact with the children until they are adults and can protect themselves from him.

While this story ends positively, there are thousands more that don't. Sally's solicitor Jenny says quite simply: "Every day I hear from women who have been trying to shield their children but have been unable to get legal aid to do so. Why are we leaving people in a position where they cannot protect their children from really serious harm?"

Pam Coughlan

Pam was very seriously injured in a road accident in the 1970s, which left her with severe physical disabilities. Unable to care for herself, she and 11 other disabled residents of a large NHS house were promised a 'home for life' if they moved to a brand-new state-of the-art NHS facility, Mardon House.

Their care was provided by the NHS until the 1990s when, out of the blue, the health authority tried to transfer responsibility for it to Social Services. By reclassifying their needs from 'health' care to 'social' care, Pam and the other residents would not only be forced to move from Mardon House, but also be means-tested and potentially start paying for their own long-term nursing care.

A devastated Pam said: "The others in the unit could not speak for themselves due to substantial physical disabilities and their relatives did not know what to do. We were desperate." Determined to fight the decision and feeling alone at the mercy of the local authority, Pam began to hunt for lawyers in the Yellow Pages.

Eventually she came across Nicola Mackintosh QC, a solicitor and founder of a law firm specialising in community care and mental capacity casework. Pam applied for and was granted legal aid and together they brought a judicial review of the decision to break the NHS's promise of a permanent home.

Over several years, Pam and Nicola battled all the way to the Supreme Court and were eventually successful. Nicola explains that "the inequality of arms is a huge issue. There is nothing more telling than representing a hugely brave claimant in court against a heavily funded public body." The immensely complex case established two important points of law that have subsequently benefited thousands of very vulnerable people. A feat that would not have been achieved without the benefit of legal aid.

Since this case was decided, lawyers are no longer paid unless successful at the first (permission) hearing; a risk that most cannot afford to take due to the highly technical work required to get to that stage. In the meantime, countless people are left without the right to redress. In the simple words of Pam's lawyer, Nicola: "What a tremendous injustice that is."

Rosaleen Kilbane

"Home is where one starts from." T.S. Eliot

Rosaleen has spent 32 years helping people to find and keep roofs over their heads. Whether it be defending possession proceedings or securing accommodation for the homeless, she is completely dedicated and regards her work as a vocation.

She sees people at their worst moments and her clients are all extremely vulnerable: "In the past year, we've had a woman who was placed in temporary accommodation by a local authority. She was a wheelchair user and couldn't get her wheelchair into the toilet. At the stage she came to us, she was starving herself so that she didn't need to go to the toilet," she says.

Rosaleen is a deputy district judge and housing specialist in a law firm in Birmingham that that does no privately paying work. All of its work is either underwritten by the Legal Aid Agency, or is free. When drastic cuts to the system were made in 2013, it became increasingly difficult for the firm to survive on work with very low fixed fee rates. But now - post Covid – they only have capacity to take one case in every four, a situation she finds heartbreakingly painful.

One of the problems is that the fees the government pays for legal aid work have not increased for more than 20 years. On top of this, they were cut by a further 10% in 2011. These low rates of pay are forcing legal professionals across the country to withdraw from providing legal aid advice because it is simply not economically viable.

As a result, the number of firms providing housing law has dropped by 28% from 346 around England and Wales in 2012, to 248 in 2021. Evictions have recommenced after a temporary ban but 23 million people live in a local authority without a single housing legal aid service. This leaves pensioners, families with young children and those with disabilities or on a low income struggling to access advice when they are at their lowest ebb.

Another problem is that debt and welfare benefits were removed from legal aid but they are areas that overlap significantly with housing issues. "We can't offer the same holistic service that we used to be able to. It's well known that poor people have clusters of problems…and sometimes the lack of legal aid to deal with the welfare benefits problem can mean that the housing problem is not solvable either," Rosaleen explains.

A lack of legal aid for preparing judicial review applications means that many potentially unlawful local authority housing decisions are no longer being challenged and families are living in inappropriate or dangerous conditions.

For rights to be real, everyone entitled to state-funded legal advice should be able to get that advice when they need it. People like Rosaleen need help for their practices to survive, or, in her words: "There's going to be nobody left to pick up the pieces because the housing lawyers will be gone."

Angela Pownall (mother of Adrian Jennings)

Angela's son, Adrian, hanged himself at his home just two weeks after being discharged from an inpatient mental health unit. He later died in Tameside General Hospital.

Angela had begged for him not to be released from the care he needed and believed that an inquest into his death would help improve procedures and prevent more vulnerable people from dying unnecessarily. As an ex-nurse and social worker, she knew and had faith in the system. However, she was confronted with a "David and Goliath situation" where she was alone against three opposing parties and their teams of publicly-funded lawyers.

Angela believed at the pre-inquest meeting that she would be talking to some managers she had been in contact with. What she found was three well-prepared barristers representing the police and two NHS Trusts. All were keen to protect their clients' reputations and avoid any findings of wrongdoing. Angela didn't even realise that she could bring someone with her for moral support.

After seeing what she was up against, Angela was put her in touch with the charity Inquest. They helped her find a local solicitor who could prepare some paperwork and connected her with a barrister to represent her. Two days before the start of the nine-day inquest, her barrister broke the news that her legal aid application had not been processed. Angela contacted the Coroner and told her she simply could not go to the inquest without help.

After a push from the Coroner, the Legal Aid Agency said it would partly fund her representation. When assessing her means, it took into consideration a family loan she had been given to pay for Adrian's funeral and Angela was forced to take out several loans in order to pay her share of the legal costs. But with a barrister being paid to help her, Angela endured the inquest and managed to secure a 'Prevention of Future Death' report, specifying things that needed to change in the system that had failed them.

Without her lawyer, Angela says that she would not have survived the inquest: "There were days when my life felt like a whirlwind. How could I have been expected to hear about my child's last moments and his autopsy and then ask questions about it? Who could physically stomach doing that? So many questions would have gone unanswered."

More than any other party, the overriding objective of bereaved families is to bring about changes to prevent future deaths, to stop others going through what they have faced. Public interest is served by their actions and the changes they bring about. And yet they are forced to fight for funding in the most painful of circumstances. The absence of equality of arms in this case, and in many others like it, is unforgivable. The cost to the public purse of providing automatic legal support would be minimal, while the cost in human misery of failing to do so, is incalculable.

Siobhan Taylor-Ward

“I did an English literature degree after having my daughter. I was a support worker for about 7 years following my A’ levels. Later I started to work with asylum seekers and vulnerable migrants. Along the way I learned how little power you have as a non-lawyer to help clients in many situations. My clients were having problems with benefits, housing and asylum and I could not resolve them without relevant legal training. So I decided to qualify as a solicitor. I had 2 children, a nine year old and a six month old baby. I decided to do the GDL part time at Liverpool John Moores University. There was no post graduate funding available for that at the time, which meant I had to pay the fees myself. I was lucky that my parents could fund half of those fees and the LPC fees but I’m very conscious of what a privilege this was and don’t think I could have proceeded without this help. I also got into debt using credit cards to pay my part of those fees and was on a low income as a paralegal. Because wages stay low in this profession I am still paying off my debts and undergraduate debts and this seriously impacts my actual income.

I then did the GDL part time and the LPC part time and worked 30 hours alongside as a case worker on the Hillsborough inquest. It was an amazing first experience as a lawyer and I knew that I wanted to qualify into civil legal aid to help the sort of clients that I had worked with as a caseworker. But qualifying wasn’t a straightforward process, and it felt like there were obstacles at every step of the way. You get your first paid work as a paralegal and then there’s another bottleneck as you compete for a training contract or a Justice First Fellowship. Even upon qualification the issue was that I had to find funding in order to ensure I would have a post-qualified job because the Legal Aid fees in Housing Law are too low to fully fund a solicitor post plus overheads. People drop out of the profession at every point, whether leaving the area of law or leaving the profession completely. Paralegals are doing such huge jobs because there aren’t enough lawyers to deal with the work coming in and this will only get worse. Caseworkers are being paid caseworker wages and are then unable to afford to qualify as a solicitor. Legal aid practices are having to limit the amount of times they can run a training contract round to every 2-3 years because of limited funding which then means there is intense competitions for the training contracts. The justice first fellowship scheme is excellent but can only support around 15 trainees a year. This also creates a bottleneck because you are only funded for your training contract but not upon qualification. I know a people who have finished the justice first fellowship and then gone into the Government legal departments. It is also a problem when women are starting families, maternity packages are just not there when compared to, for instance, universities or Government work. The profession is losing so many good people because of the constant concern about whether the job is sustainable. All of which is compounded by other issues in the country; rent increases, inflation, lack of proper retirement provision and the soaring cost of housing. As a single parent on a Legal Aid lawyer’s wage it is hard to see how this profession can be sustainable long term if the situation does not improve.”